Home » Posts tagged 'Healthcare Delivery'

Tag Archives: Healthcare Delivery

Ephemeral Hospitals, Enduring Insights: Healthcare at the Kumbh.

– Dhruv Kazi , MD, MSc, MS

Savitri Devi, a 57-year-old mother of two, began her journey to the Mahakumbh in a small village in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. She traveled 12 hours by train with her husband in order to take part of Hinduism’s most spectacular celebration, a bathing ritual performed by millions at the confluence of India’s holiest rivers.

This Kumbh is arguably the largest human gathering of all time, swelling to 30 million on the holiest day of the festival, and totaling to as much as 100 million over the course of the entire 55-day event. By those estimates, if the Kumbh were a nation, it would be the 12th most populous in the world.

Delivering health care to 100 million people is an enormous task anywhere, but it’s even more challenging when the city – and hence its hospitals – must be temporary. By the end of March, the entire city will have been dismantled. By the time the monsoons arrive, almost the entire area of the Kumbh will be reclaimed by the rising rivers.

Ten sector hospitals are constructed specifically for the Mela. Each of these clinics comprises a collection of large tents that house an outpatient clinic and a 20-bed inpatient unit. The hospitals operate 24/7 throughout the duration of the festival, though workload peaks with population surges around the most auspicious bathing days. Each day between 500 and 800 patients arrive and are seen – briefly – by one of the physicians on duty. These doctors come from government clinics from around the state and are assigned to the Mela for two months apiece. The doctors work in 8-hour shifts, have no official days off, and sleep in tents that are pitched adjacent to the clinic. Each hospital has a pharmacy with over 90 drugs that are provided free of charge.

The centerpiece of this healthcare delivery system is the central hospital in sector 2. Here patients can be seen by a range of specialists, including orthopedics, surgery, and obstetrics. There is a 100-bed inpatient unit and a 2-bed ICU. Diagnostic tools such as X-ray, ultrasound and electrocardiograms are available. Dr Srivastava, who supervises the entire healthcare delivery system of the Mela is based here, and receives daily reports on the number of patients seen at each of the smaller sector hospitals.

Connecting these hospitals is a fleet of more than 100 ambulances which are responsible for transferring patients who need specialized care from the sector hospitals to the central hospital. The ambulances, like the doctors who staff the hospitals, have been drafted from community health centers across the state. Each ambulance arrives with its own driver, who is then provided with accommodation at the Mela. The drivers, who receive no additional training for the Kumbh, seem to take great pride in their work. I had the opportunity to meet with Arvind Kumar, a 40-year old from Ajamgadh, who has been at the Mela for a month. He proudly showed me his log – a detailed record of trips made (including point of origin and destination), distance traveled, and fuel costs. There were no patient records in the ambulance loArvind Kumar, Ambulance Driver in Sector 2.

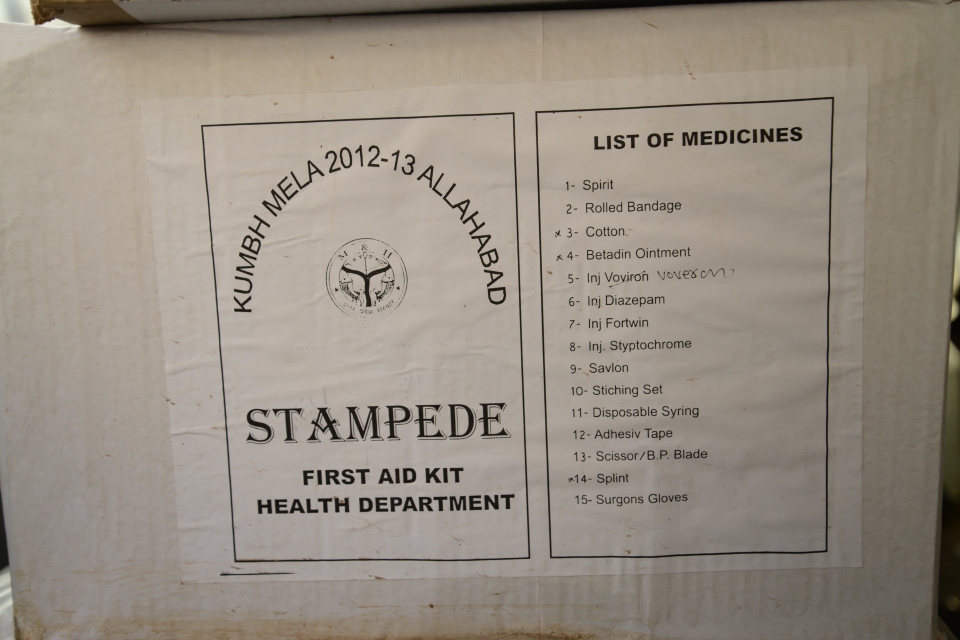

The ambulances themselves appear to be new and well maintained, with clean stretchers to transport patients and a hand-held radio device for communicating between ambulances and with central dispatch. Each ambulance carries an oxygen tank, a host of emergency medications, and four disaster kits: for drowning, burns, bomb blasts and stampedes. It is evident that a reasonable amount of thought has gone into designing each of the kits, but there are no paramedics (which is typical in India) and a physician must accompany seriously-ill patients. Based on an examination of Arvind Kumar’s log book, it appears that an ambulance makes 5-6 trips a day.

So what does an interdisciplinary team from the Harvard School of Public Health have to contribute to an ancient congregation of millions of pilgrims which seems to be running remarkably smoothly? The answer is simple: Data.

During our visits to the hospitals, we noted that the doctors manning the outpatient posts see up to 800 patients a day – and many times that figure on bathing day – and are clearly overstretched. Lines of patients preclude even a cursory medical examination. No vital signs are documented and there are no stethoscopes in sight. On the other hand, inpatient units were almost uniformly unoccupied. Row after row of hospital beds, neatly folded red blankets, and I.V. poles stand untouched. On our visit two days before the peak bathing day, we saw only the occasional hospitalized patient – a testament to excess capacity in the system.

This striking contrast between the excess capacity on the inpatient side and extreme shortage of manpower on the outpatient side is the result of an information vacuum about the disease burden and clinical resource utilization in this patient population. Poor data result in poor planning, and ultimately a lopsided distribution of resources.

Our team’s work begins to address this critical gap. By digitally capturing patient encounters at four sector hospitals, we are mapping healthcare delivery at the Mela. We have three broad objectives in doing so.

First, we want to show that it is feasible to use low-cost technologies to gather quality data in a resource-scarce setting. The fieldwork for the project is being done with a small team of passionate (and remarkable) students wielding a handful of iPads. If we can do it, the government certainly can too.

Second, by providing a snapshot of the healthcare needs of the attendees, we hope to help optimize resource management. For instance, knowing that less than 1 percent of outpatients get admitted to the hospital would suggest that the most cost-effective strategy in the future would be to station more physicians in outpatient clinics and offset the costs by planning for fewer hospital beds at sector hospitals. The reserve capacity needed for epidemics should be centralized at the district hospital.

Third, and most importantly, real-time analysis of the data provides an effective surveillance tool – an early warning system for impending epidemics. This is no easy task in a setting such as this where the population at risk – i.e., the number of pilgrims at the Mela – varies greatly from day to day. When analyzed methodically, differences in patterns of disease between hospitals and over time can help distinguish a signal of an epidemic from the noise of random variation. This tool can help public health officials deploy preventive strategies in a timely manner to avert a a widespread outbreak.

Conventional wisdom holds that generating quality data in resource-scarce settings is prohibitively expensive in resource-scarce settings, and that ad hoc planning is therefore unavoidable. By collating and analyzing data from over 20,000 patients, we are turning that assumption on its head. Although the entire Kumbh Nagar (township) will have been dismantled by the end of March, the insights we gain from the analysis of the data will endure. With the support of the Harvard School of Public Health and the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, we hope to empower future Kumbh organizers with the information they need to cost-effectively safeguard the health and well-being of the millions who will follow in Savitri’s footsteps for generations to come.