Kumbh Mela and Burning Man: What the world’s two craziest pop-up cities have in common

Click here to read Logan Plaster’s blog post in Quartz on the similarities between the Kumbh Mela and Burning Man festivals.

The Sangam of Three Waters: Clean, Grey, and River

– Michael Vortmann

Two additional bathing days have passed on the 10th and 15th of February, and after two hard days of rain, our colleagues still at the Kumbh say the City is significantly emptied from its estimated peak of 30 million.

One of the key logistical challenges at the Kumbh is managing water flows for the millions of people who come to bathe. Qualitative observations indicate the government sinks boreholes and runs extensive piping to supply each Akhada area with drinking water. The Akhadas then build smaller networks of piping for spigots for personal use. Some these spigots can be found at irregular intervals facing the street for public consumption. In addition to the public supply there are private companies giving away free water. Many of the clinics have an Aquaguard (a brand-name UV purification system) spigot in a kiosk immediately outside their gates. Some intersections host manned water stations provided by Tata (a ubiquitous manufacturer) that provide samples in small cups.

In addition to the extensive systems providing clean drinking water, greywater also has separate and actively managed catchment systems. Runoff from spigots is collected in sandbag-lined ponds that flank the roads. The water is treated with pesticides and lime, pumped into trucks, and used to spray down the grounds to mitigate the considerable amounts of dust and smoke created by the milling crowds.

In spite of the well-planned segregation of clean and greywater, and frequent sources of clean water, people still drink from the Ganga and sometimes collect greywater from the trucks watering down the roads – this in spite of large written warnings to the contrary.

A question that arises is whether the efforts to segregate different water streams and provide clean drinking water translates to a reduced burden of diarrheal diseases, a known side effect of consuming contaminated water. The overall percentage of diarrheal illness presenting to the clinics we surveyed was relatively low – about 5% of total presenting complaints. Controlling for the massive influx of people on bathing days, we would like to see if the percentage of diarrheal cases increases relative to the population, and whether this correlates to the cleanliness of the water. A small subproject of the public health team has plated water collected from the Ganga both upstream and downstream of the major bathing areas to see the coliform and E coli counts in the water – as a marker of human fecal contamination and general cleanliness. We suspect the water is dirtier when millions bathe in it but will this translate to more diarrheal disease? And if we discover the river is in fact dirtier, and we know people are drinking it, an even more interesting question is why not?

EMcounting the Mela: From Chennai to Prayag*

– Satchit Balsari, HSPH Kumbh Mela Team Leader

*With apologies to Professor Eck 🙂

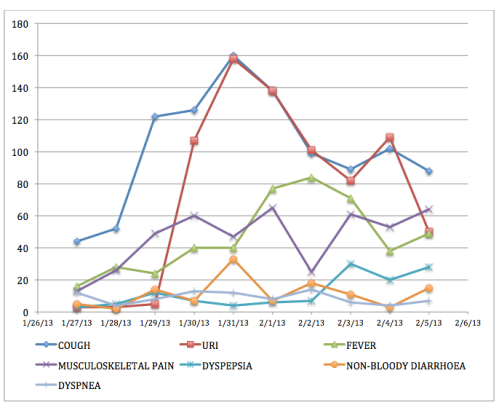

Yesterday, our team crossed the 30,000 mark. Since January 27th, 2013, the four sector hospitals that we have been following have seen over 30,000 patients. The hospital in Sector 11 has seen four times as many patients as that in sector 4. Upper respiratory complaints continue to dominate the presentation to the clinics (about 32%), with fever and musculoskeletal pain close behind. Over 58% of the medications dispensed were analgesics (pain medications) and a quarter were anti-histamines, all of which are available over the counter, without requiring the presence of a physician.

As we have repeatedly said on this blog, the political will and commitment to making the Mela a success is unprecedented, yet the staggering crowds that come to the Mela repeatedly overwhelm the system: the 30-120 second window for doctor-patient interaction, as the current data reveals, is far from the ideal that the Mela authorities had aspired to.

The size of this data set will allow the authorities to examine several seminal issues surrounding healthcare delivery: prescription practice, resource allocation, epidemiology, and patient behavior at the sector hospitals in the Mela. Our analysis will hopefully influence planning and resource allocation for future Melas. Furthermore, having successfully demonstrated that it is indeed possible to collect such large quantities of data in this chaotic environment, we hope to work with the National Disaster Management Authority of India to consider piloting digital data collection in future mass gatherings in India.

As Dhruv points out, “quality data fosters accountability.” And quality data will help local authorities explore a whole range of new possibilities: engaging more mid-level providers and junior practitioners to see the large volume of patients, reserving the physicians’ time for the more acute cases; piloting cleaner cooking measures, educating the pilgrims on clean water, sanitation, hygiene.

Soon we will bring our surveillance at the sector hospitals to a close, but before we do that, we wanted to share the story of our team with you: the story of 20 public health and medical students from Allahabad and Mumbai who, armed with a handful of iPads, two mobile hotspots, five broken rental bikes, one portion innovation, two portions gumption, and a diehard commitment, logged over 1800 hours of work in 20 days to help this team achieve its goals.

The tool we used to log data is called “EMcounter” – it was originally developed by emergency residents at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital (NYP) in 2006 to “count” the medical emergencies that presented to casualty wards of hospitals in India that were moving away from traditional one room receiving rooms to more sophisticated emergency departments staffed by trained emergency physicians. After its initial successful run at Sundaram Medical Foundation in Chennai, in 2007, EMcounter stayed dormant for a few years until a mobile tablet-based version was tested in South Sudan in 2012. EMcounter now had the capacity to collect data off-line on mobile devices, and could also analyze raw data in real time, as soon as it was uploaded. In other words, we needed several iPads to digitize the records at the sector hospitals, and mobile hotspots to guarantee generous internet availability to the data collectors. Both easily acquirable. Indian companies rent iPads, and mobile hotspots are an inexpensive investment.

What we needed was the official nod to collect this data, and an army of field staff to digitize the patient records. The National Disaster Management Authority of India provided the former and good Kumbh Mela karma the latter. Namita introduced us to Nutan Maurya, who had already been working with the other Harvard teams. As early as December, Nutan had lined up students from Allahabad’s Sam Higginbottom Institute of Agriculture Technology and Sciences. The Agriculture Institute (as it was formerly known) offers India’s oldest two-year Masters in Public Health. Senior specialists from NDMA, Naghma Firdaus, helped us identify a contact person in the Allahabad Medical College – Dr. Shraddha Dwivedi, also superintendent of Allahabad’s largest public hospital, Swaroop Rani Nehra Hospital. Dr. Shraddha Dwivedi who extended this team her enthusiastic and whole hearted support, made available a steady stream of rotating medical interns to augment this team.

Initially we wanted to cover all 10 sector hospitals and build some redundancy into the staffing. We were looking for more field researchers. Like our Allahabad group, future team members needed to be familiar with medical jargon, the public sector healthcare system, bilingual, and at ease negotiating the potential morass of bureaucratic red tape and obstructionism they may encounter. By then we had already made several trips back and forth between various authorities all of whom supported the project and all of whom were unable to provide us the requisite permission, until the NDMA stepped in.

Over serendipitous chai in the home of a loving Parsi family in South Mumbai, in an old house overlooking Marline Lines and Saifi Hospital, during a sort-of reunion of the Rotaract Club of the Caduceus, five medical students from Maharashtra thought it worth their while to commit their time and resources to spend two weeks at the Kumbh Mela in Allahabad. The Rotaract Club of the Caduceus, of which I was also once a member, was started in 1997 as a non-governmental organization committed to community service. What started as a motely group of 15 medical students is now a bustling organization of over 120, that conducts cataract camps, large fund-raising drives, and sometimes launches a nation-wide campaign to recruit student volunteers to conduct research in the world’s largest gathering. Panjak Jethwani and Ahmed Shaikh assembled two impressive teams of medical students from Mumbai, Nagpur and Allahabad, after vetting applications from across India and Nepal.

Our team was now almost ready. There was one missing ingredient. Aaron Heerboth.

India Today has written about Aaron’s exercise routine at the Mela and German television has done a segment on Aaron given instructions to the local team. Aaron is a graduating medical student from Weill Cornell Medical College. He is now almost a Kalpavasi! He is certainly the Harvard Kumbh Mela Team’s longest resident member at the Nagri. Having arrived with the initial team in January, by the time the second public health team reached the Mela in early February, Aaron had consolidated his daily routine at the Mela: it involved running long distance between the sector hospitals, dodging cows, crowd and sadhus, jumping over grey water ditches and steering his moped away from the slushy mud that collects at the edges of the metal plates lining the roads.

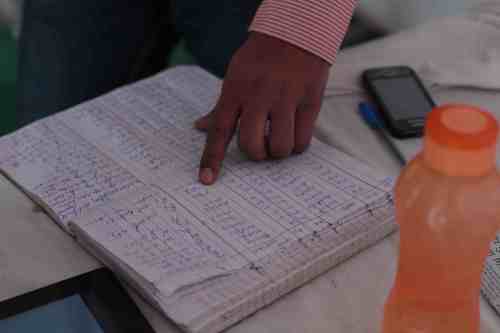

By February we had realized that the large numbers of patients presenting at the clinics everyday would make it impossible for us to cover all ten clinics. We simply did not have the manpower to do that. We chose instead to pick four representative hospitals based on their diversity of location, accessibility and patient volume. Teams of two, three or sometimes four field staff were required to collect data at these centers. And every day, the overworked Mela physicians had to be gently reminded the importance of documenting at least the chief complaint and the medication dispensed. That was the limit of the medical chart. To expect anything more was foolhardy – given the few seconds that the physicians had per patient encounter it was no surprise that more could not be recorded. Interpreting handwriting, chasing down missing registers, drawing vertical columns in the ledger books and motivating the field researchers every day, sometimes several times a day constituted Aaron’s morning routine.

Here are excerpts from Aaron’s notes to us:

“After somewhat clumsily navigating Allahabad’s shared rickshaw system this morning (which involved several transfers and numerous price negotiations) and a good 3 KM run through crowds of Sadhus, I arrived on site at sector 4 just after 9am to meet our eager public health students.

It appears that today we continue to be (somewhat) reliably up and running with Kumbh Mela EMcounter! Through numerous polite discussions, we have resolved some major physician handwriting issues at sectors 4 and 13, and our four public health students stationed at those hospitals are not having any significant problems. However, one team of two people with one iPad seems somewhat inadequate for sector 4 if we don’t want to overburden our data collectors. Sector 4, however, is on the main road to the Sangam, and has been seeing about 700 patients per day. Hopefully with thearrival of the Mumbai reinforcements, we can have more iPads andpeople at this site. I also think that at all sites, a larger show of presence will help motivate the physicians to document better records.

At 10:30 I had another Sadhu-dodging run to meet up with the medical interns covering sites X and Y. Things also appear to be going quite smoothly there. Unfortunately, at sector X the physicians are refusing to record chief complaint/diagnosis. I spoke to the physician in charge and tried to explain the big picture importance of recording this data (and I also mentioned that his superiors request it), and he seems to understand, but we will see where this goes.

Logistics summary for today:

Sector 11: Approximately 300 patients, all recorded. Started out with two iPads and 4 people and finished entering the 300 patients in about two hours.

Sector 13: Approximately 350 patients, half recorded wanted them to start fresh today but this was a miscommunication. They should be able to cover all patients from now on. I do feel bad because I very rarely make it to that site given that it’s about 4 km from the others. I did run there once today to thank the physicians for working well with our team.”

Aaron’s run through the Mela starting assuming legendary proportions – a news article mentioned it, bloggers blogged about it, and a satirical piece even disparaged it. Another few weeks and Aaron would soon become the “Running Baba.”

Aaron reported on the Mumbai team’s arrival: “Today was our first day in the field with the new Mumbai students as well as our first day with a fresh batch of Allahabad students. The Mumbai students were actually able to rent a rickshaw for the day and visit each site with me. They were not enthused about my proposed running method. Our rickshaw tour helped orient them to the very disorienting Kumbh area, and they also assisted with several hundred patient entries at the busy sectors 11 and 12. The dust and poor roads seemed to get the best of a couple of them, but overall they are very excited to be on board.”

Ahmed’s diary:

“It’s been 24 hours of alot of travel and dust. We started off from Lucknow in the train, only an hour late. Great journey. Kind of gave us the idea of the general infrastructure and health conditions that we were heading into. Allahabad at 10pm and 9°C. The owners of the place picked us up as they promised earlier, although I don’t remember them mentioning they’re gonna be drunk while they do it. The place is fabulous. Great rooms. Great bathrooms. But….. No water heater. Every time we touch water, it’s like the limb might fall off. Luckily I carried a heating coil, the services of which I’m offering to my team members in return for rent free stay over these fifteen days. The matter is under negotiations. Aaron was super nice to come by and meet us late night just after we arrived. It was great to get oriented the night itself. We downloaded the EMcounter application and had a short demo of how it’s used . He’s made a great network of people who help him get around places. Not that he needs them to do it.

Next morning:

We hired a 6 seater rickshaw for Aaron to show us around the entire Kumbh site and the medical facilities. The medical facilities are great. They’ve got great inpatient wards, some would say, even better than the ones we have in established tertiary care hospitals.

This is how we work:

The doctors are required to keep a record of all patients and medicines administered. This register, has poorly recorded data. We borrow the register from the day before and feed it into the application. We are in the process of getting a signed and stamped letter from the highest health authority of the Kumbh.”

The rickshaws didn’t last long. Boys will be boys. And soon, the team had rented a few scooters that they used to navigate the crowds and cows and Mahavir, Jagdish and Triveni Roads up and down the Kumbh Mela. Little by little, our fantastic team of students from across India were learning the principle of public health field research: tenacity, ingenuity, patience, persistence, improvisation, and innovation.

We left a week ago, but the project continues. This week the team met Rishi Madhok, another emergency physician from NYP, and the technical lead for EMcounter, who arrived in Allahabad a newly married man, straight from his honeymoon. Rishi will work with the local team to expand the survey to the Central Hospital in Sector 2 where we will capture a wholly different set of pathologies – sicker patients with more complex medical problems presented to the Central Hospital.

We will remember our time at the Kumbh Mela fondly. The chanting, the smells, the music emanating from every street. The dense crowds on Mauni Amavasya. The millions that stood in waist deep waters and raised their palms to the sun as millions before them always have. It was spectacular. It was poetic. And it was profoundly humbling.

But interacting with our local team was equally, if not more, exhilarating. Reading Avnish’s policy recommendations for future Melas, following Abhishek on a tour of his hospital wards, listening to Aditi oscillate between psychiatry and pulmonology as her career choice, supporting Ahmed as he worried about the incoming team-mates that cancelled their tickets after the stampede, observing Aaron navigate his way around the Mela like he was strolling on the lower east side of Manhattan, and watching Ghanshyam engrossed over a tuberculin syringe dripping E.coli contaminated water onto a culture plate, we were reminded of our collective pursuit of knowledge — unfettered by age, gender, caste or creed.

At the world’s largest gathering of faith, we had bonded over science.

The Times of India Highlights HSPH Team’s Findings

Read the full article here: “Harvard doctors give Kumbh Health Facilities thumbs up”

HSPH Kumbh Mela Team Featured in The Telegraph India

Read the full story here:

http://www.telegraphindia.com/1130212/jsp/nation/story_16551921.jsp#.URr8ZY4p-S0

Ephemeral Hospitals, Enduring Insights: Healthcare at the Kumbh.

– Dhruv Kazi , MD, MSc, MS

Savitri Devi, a 57-year-old mother of two, began her journey to the Mahakumbh in a small village in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. She traveled 12 hours by train with her husband in order to take part of Hinduism’s most spectacular celebration, a bathing ritual performed by millions at the confluence of India’s holiest rivers.

This Kumbh is arguably the largest human gathering of all time, swelling to 30 million on the holiest day of the festival, and totaling to as much as 100 million over the course of the entire 55-day event. By those estimates, if the Kumbh were a nation, it would be the 12th most populous in the world.

Delivering health care to 100 million people is an enormous task anywhere, but it’s even more challenging when the city – and hence its hospitals – must be temporary. By the end of March, the entire city will have been dismantled. By the time the monsoons arrive, almost the entire area of the Kumbh will be reclaimed by the rising rivers.

Ten sector hospitals are constructed specifically for the Mela. Each of these clinics comprises a collection of large tents that house an outpatient clinic and a 20-bed inpatient unit. The hospitals operate 24/7 throughout the duration of the festival, though workload peaks with population surges around the most auspicious bathing days. Each day between 500 and 800 patients arrive and are seen – briefly – by one of the physicians on duty. These doctors come from government clinics from around the state and are assigned to the Mela for two months apiece. The doctors work in 8-hour shifts, have no official days off, and sleep in tents that are pitched adjacent to the clinic. Each hospital has a pharmacy with over 90 drugs that are provided free of charge.

The centerpiece of this healthcare delivery system is the central hospital in sector 2. Here patients can be seen by a range of specialists, including orthopedics, surgery, and obstetrics. There is a 100-bed inpatient unit and a 2-bed ICU. Diagnostic tools such as X-ray, ultrasound and electrocardiograms are available. Dr Srivastava, who supervises the entire healthcare delivery system of the Mela is based here, and receives daily reports on the number of patients seen at each of the smaller sector hospitals.

Connecting these hospitals is a fleet of more than 100 ambulances which are responsible for transferring patients who need specialized care from the sector hospitals to the central hospital. The ambulances, like the doctors who staff the hospitals, have been drafted from community health centers across the state. Each ambulance arrives with its own driver, who is then provided with accommodation at the Mela. The drivers, who receive no additional training for the Kumbh, seem to take great pride in their work. I had the opportunity to meet with Arvind Kumar, a 40-year old from Ajamgadh, who has been at the Mela for a month. He proudly showed me his log – a detailed record of trips made (including point of origin and destination), distance traveled, and fuel costs. There were no patient records in the ambulance loArvind Kumar, Ambulance Driver in Sector 2.

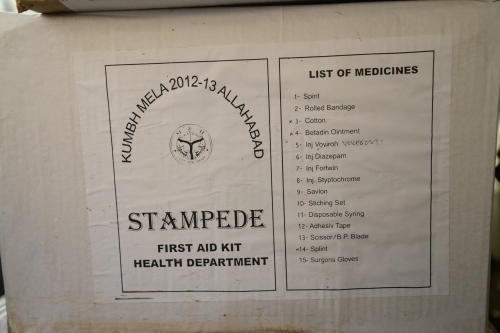

The ambulances themselves appear to be new and well maintained, with clean stretchers to transport patients and a hand-held radio device for communicating between ambulances and with central dispatch. Each ambulance carries an oxygen tank, a host of emergency medications, and four disaster kits: for drowning, burns, bomb blasts and stampedes. It is evident that a reasonable amount of thought has gone into designing each of the kits, but there are no paramedics (which is typical in India) and a physician must accompany seriously-ill patients. Based on an examination of Arvind Kumar’s log book, it appears that an ambulance makes 5-6 trips a day.

So what does an interdisciplinary team from the Harvard School of Public Health have to contribute to an ancient congregation of millions of pilgrims which seems to be running remarkably smoothly? The answer is simple: Data.

During our visits to the hospitals, we noted that the doctors manning the outpatient posts see up to 800 patients a day – and many times that figure on bathing day – and are clearly overstretched. Lines of patients preclude even a cursory medical examination. No vital signs are documented and there are no stethoscopes in sight. On the other hand, inpatient units were almost uniformly unoccupied. Row after row of hospital beds, neatly folded red blankets, and I.V. poles stand untouched. On our visit two days before the peak bathing day, we saw only the occasional hospitalized patient – a testament to excess capacity in the system.

This striking contrast between the excess capacity on the inpatient side and extreme shortage of manpower on the outpatient side is the result of an information vacuum about the disease burden and clinical resource utilization in this patient population. Poor data result in poor planning, and ultimately a lopsided distribution of resources.

Our team’s work begins to address this critical gap. By digitally capturing patient encounters at four sector hospitals, we are mapping healthcare delivery at the Mela. We have three broad objectives in doing so.

First, we want to show that it is feasible to use low-cost technologies to gather quality data in a resource-scarce setting. The fieldwork for the project is being done with a small team of passionate (and remarkable) students wielding a handful of iPads. If we can do it, the government certainly can too.

Second, by providing a snapshot of the healthcare needs of the attendees, we hope to help optimize resource management. For instance, knowing that less than 1 percent of outpatients get admitted to the hospital would suggest that the most cost-effective strategy in the future would be to station more physicians in outpatient clinics and offset the costs by planning for fewer hospital beds at sector hospitals. The reserve capacity needed for epidemics should be centralized at the district hospital.

Third, and most importantly, real-time analysis of the data provides an effective surveillance tool – an early warning system for impending epidemics. This is no easy task in a setting such as this where the population at risk – i.e., the number of pilgrims at the Mela – varies greatly from day to day. When analyzed methodically, differences in patterns of disease between hospitals and over time can help distinguish a signal of an epidemic from the noise of random variation. This tool can help public health officials deploy preventive strategies in a timely manner to avert a a widespread outbreak.

Conventional wisdom holds that generating quality data in resource-scarce settings is prohibitively expensive in resource-scarce settings, and that ad hoc planning is therefore unavoidable. By collating and analyzing data from over 20,000 patients, we are turning that assumption on its head. Although the entire Kumbh Nagar (township) will have been dismantled by the end of March, the insights we gain from the analysis of the data will endure. With the support of the Harvard School of Public Health and the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, we hope to empower future Kumbh organizers with the information they need to cost-effectively safeguard the health and well-being of the millions who will follow in Savitri’s footsteps for generations to come.

In the Aftermath of the Stampede

– Satchit Balsari, HSPH Kumbh Mela Team Leader

February 11, 2013

It’s 1:30am and we are now in Benaras. We delayed our morning departure to spend another day at the Kumbh.

Mauni Amavasya was not the uneventful day the organizers had hoped it would be. Officials say that 30 million people (one and a half times Bombay’s population) took a peaceful dip at the Sangam. Hundreds of thousands of pilgrims lined Parade Road to watch the processions roll by – the Naga sadhus, the Shankaracharyas, and the mahants, from Hinduism’s various denominations, and from India’s far flung corners. There were people everywhere – on the pontoons leading up to the Sangam, on the pontoons bringing them back safely after they holy dip, on Triveni Road, and Jagdish Road and Mahavir Road and every road that intersected every other road in the Nagri, on the hill next to the Sangam, inside the Akharas and outside the Akharas, on Shastri Bridge that spanned the wide Ganga, on the roads that led to the Nagri, on the roads that led away from Allahabad, on the 6000 buses waiting to depart from the seven bus stations, in the Ganga, in the Yamuna, in the Sangam and besides the Sangam. And on a footbridge over platform 6 at the railway station. It was the world’s biggest fair. Everyone was invited. And everyone came.

The atmosphere was festive: the energy palpable, the excitement contagious, and the masses patient. Men, women, children, the elderly and the frail all headed to the Sangam. There was color everywhere: bright reds and greens and yellows and oranges. On the turbans, on the sarees, on the flags, on the walls. And there were songs: incessant, loud and mostly pious. And smells: of incense, and prasad and marigolds and humanity. And the millions walked to the Sangam with a purpose. They were resolute in step, but not hurried; they were carefree but cautious. They were happy. They were accommodating. They were joyous. The sight from 30 feet atop the watch tower at the Kumbh was one to behold:a dense, teeming mass of Snaanarthis (bathers), punctuated by billowing bright sarees drying in the wind. Bathers frolicked in the water. Commuters lounged where they could. Villagers tried to sell their cows for Godaan. The otherwise demure Indian homemakers stripped down to their petticoats to bathe in the river. The sadhus sat atop tractors and chariots and colorfully decked lorries. Commerce flourished. Sins perished.

It was indeed a beautiful day in Prayag. As it has always been for centuries when the Mela arrives at the Triveni Sangam. Except in 1954 – when a rogue elephant barreled into a dense crowd that had gathered to see their beloved Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. The ghost of the resulting stampede has loomed over the Allahabad Kumbh ever since. No Mela adhikari, no Kumbh sevak, no politician, no government servant, no Allahabad nivasi wants another mishap at the Kumbh.

The sun was slipping behind the tent-tops. Everyone breathed a sigh of accomplishment, of satisfaction, and of relief. Another big bathing day had come and gone. And millions had been returned home safely. Almost.

The large notice board in the railway booking office compound in Sector 2 of the Kumbh Mela had 202 train options for people to choose from. Late last evening, when the Rajdhani arrived, thousands of eager commuters rushed up the sole footbridge from platform 1 to platform 6. Police tried to hold back the crowd. Some say a lathi (baton) may have been raised. No one really knows what happened, whose foot slipped first, who toppled next. But several hours later, when the last ambulance pulled by at SRN Hospital at 2:30am, 36 pilgrims were dead, over thirty injured. Three were in critical condition.

Two nights ago, a journalist from one of the world’s leading dailies was lamenting how hard it was to report on the Kumbh. That millions had gathered in India once again for a holy dip in the Ganga wasn’t new. Wasn’t captivating. Wasn’t interesting. The government’s worst nightmare had just come true: the Kumbh had suddenly become interesting.

“Horror at Kumbh” screamed the headlines in one of India’s largest dailies. And we, the HSPH Public Health team, shared the organizers’ disappointment, heart-break and dejection.

Thousands of people work for months on end to make the Kumbh Mela a success. The statistics are staggering, and yet, the Indian bureaucracy, sometimes fatalistic and often times laissez-faire – puts its muscle behind the Kumbh. The Kumbh Mela sees more resources, more planning, more implementation and more goodwill than any other large public project in India. It is tempting, very tempting, to therefore attribute the footbridge stampede to a freak but unfortunate accident that may scar the 2013 Mela forever. But to do so would be erroneous, for we believe that the footbridge accident is a symptom of a more pervasive malaise in the planning process, not unique to the Kumbh. The dismissive, overconfident, exclusive, hierarchical, rigid planning processes so rampant across institutions in the region, are as responsible for the foot-bridge stampede, as they are for the bottlenecks from the main avenues to the pontoon bridges, for hundreds that get traumatized every day running from pillar to post to search for their lost relatives at the Kumbh, for the thousands that get prescribed medications without so much as a cursory glance from their physician and for the oxygen tanks in the ambulances that can’t be unlocked without a key.

We will write more about these and related issues in the coming days.